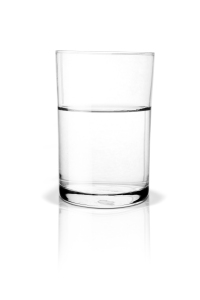

A psychologist walked around a room while teaching stress management to an audience. As she raised a glass of water, everyone expected they’d be asked the “half empty or half full” question. Instead, with a smile on her face, she inquired: “How heavy is this glass of water?”

Answers called out ranged from 8 oz. to 20 oz.

She replied, “The absolute weight doesn’t matter. It depends on how long I hold it. If I hold it for a minute, it’s not a problem. If I hold it for an hour, I’ll have an ache in my arm. If I hold it for a day, my arm will feel numb and paralyzed. In each case, the weight of the glass doesn’t change, but the longer I hold it, the heavier it becomes.”

She continued, “The stresses and worries in life are like that glass of water. Think about them for a while and nothing happens. Think about them a bit longer and they begin to hurt. And if you think about them all day long, you will feel paralyzed – incapable of doing anything.”

Remember to put the glass down.

This is good advice for many people. For many of us, the stresses and worries in life are similar to a glass of water. We can put  the glass down when we need a break. We can take vacations from work, relax during and ‘evening in’, and forget about whatever is stressing or worrying us for a little while. This sort of behavior is healthy for us to practice and provides us with the rest we need to succeed in life.

the glass down when we need a break. We can take vacations from work, relax during and ‘evening in’, and forget about whatever is stressing or worrying us for a little while. This sort of behavior is healthy for us to practice and provides us with the rest we need to succeed in life.

For other people, however, ‘putting the glass down’ may not be possible. For some, it may be practically impossible to take a break or a vacation from the stresses and worries in their life. These people are the global poor all over the world. The people who, in local currency equivalents, consume less than $2 per day – that includes every major dimension of consumption: food, housing, education, health, security, transportation, etc.

This is the broad point of Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir’s book Scarcity: Why Having So Little Means So Much. Sendhil (a behavioral economist at Harvard) and Eldar (a psychologist at Princeton) demonstrate through lab and field experiments how the mind is taxed by stresses and worries in our life. When humans are busy, or sleep deprived, or poor we focus extra mental “bandwidth” toward whatever is stressing us. This allows us to do amazing things on a deadline or despite a lack of sleep but it takes attention away from other important aspects of life as our minds only have so much bandwidth. The kicker is the busy and the sleep deprived can take a vacation or sleep in on a Saturday morning; the poor however, can’t take a vacation from their poverty. They can’t put the glass down.

This is an important understanding in itself, but there is increasing evidence that there is an added (perhaps secondary) effect of poverty on human cognition.

Although is is not a standard view in economics, many development economists are coming to the understanding that individual desires and economic behavior are often influenced by historical experience and social observation. Rather than existing in isolation, so-called consumer preferences are conditioned by memorable experiences or are formed by comparison with others. In this vein, for many of the poor around the world the environment in which they life (i.e. multi-generational life-stealing poverty) may influence their behavior specifically as it concerns decisions to invest in the future.

In short, the most devastating aspect of global poverty may the critical lack of aspirations, or more broadly hope in the future.

There is a growing literature on the economics of hope (see here, here, here, and here). This literature can be briefly summarized in the conclusion of an important series of lectures given in 2012 by Esther Duflo, an economist at MIT:

A little bit of hope and some reassurance that an individual’s objectives are within reach can act as a powerful incentive. On the contrary, hopelessness, pessimism, and stress put tremendous pressure both on the will to try something, and on the resources available to do so.

I am currently in Myanmar (a place where George Orwell’s grandmother lived and where he himself spent several years working for the Imperial Police). I am here working to implement a field experiment to measure the psychological and economic effects of hope. The study is still in preliminary stages and I’ve spent the last several days in open ended interviews with small-holder farmers and landless villagers in the rural areas of Mon State.

Myanmar is unique and fascinating place to study the formation of hope at the present time. In 2011 democratic elections led to political and economic reforms. While opportunity abounds in many places as prices of important goods and services (i.e. vehicles, electricity, 3G mobile connectivity, health care, ect.) become more affordable due to the opening of the country to global trade, some areas of the country are still constrained and lack access to this opportunity.

I met with a family yesterday that expresses these challenges all too well. The family is Christian in a country and village that is predominately Buddhist. They live on the grounds of their local church for free and, in return, maintain the church property. They own no land and rent no land. Both the mother and father are day laborers and both are currently unable to find work. The mother forages in the forest for bamboo shoots and mushrooms. They have six children, two of which have migrated to Thailand to find work. None of their children have completed formal education and the chances aren’t great for the younger children, according to the father.

When I asked when the last time the family was happy the father responded, “When we are able to have a good meal”. When I asked how often that happened, he responded, “About twice a week”.

I asked what would make their family happy in the future, the father responded, “Last year the church gave each family $100, we’d be happy if that happened again”.

Psychologists say hope is comprised of three elements: goals, agency, and pathways. This family, at least anecdotally, lacks each of these elements. Their aspirations for the future are low and their goals rely heavily on other people.

George Orwell once wrote, “Within certain limits the less money you have the less you worry”. As I sit in the setting of his classics Burmese Days and Shooting an Elephant I have come to realize, he was wrong. The global poor are subject to incredible levels of stress: diseases, expectantly for children, are more likely to be life-threatening; crop failure can lead to starvation. And as shown by the work of Sendhil and Eldar stress makes good decision-making harder.

Perhaps most importantly, the poor lack the institutional environment which fosters good decisions. People, everywhere, underestimate the benefits of education, struggle to save their income, and spend on health care. In rich countries, however, kids going to school is a common social norm; direct deposit and pension systems make personal finance and saving for retirement something many don’t even think about most days; clean and drinkable water comes out of every tap and childhood immunization appointments are automatically set up. Poor countries provide few such prompts and many poor people around the world don’t experience these luxuries.

David Brooks (I know, I know. He’s a polarizing figure) recently wrote: “The world is waiting for a thinker who can describe poverty through the lens of social psychology”. I think the wait is over, the thinkers are here. It’s the folks working on the economics of hope and the psychology of poverty.

Leave a reply to Poverty Fault Lines: Towards an Understanding Persistent Poverty | Jeff Bloem Cancel reply